Alignment, with a Twist

How Gary Gygax, plus a forty-five degree rotation, can clarify the moral landscape, (including in American politics).

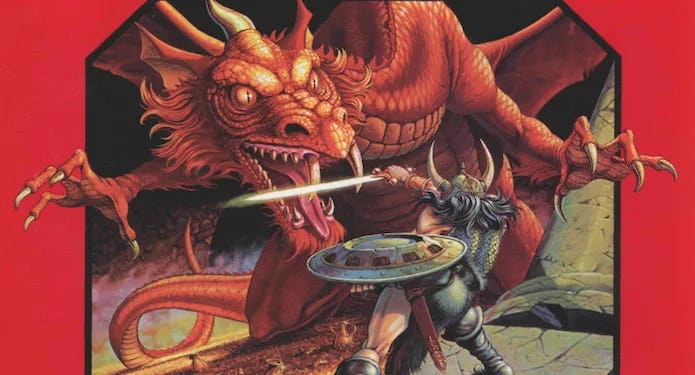

I sort of played Dungeons and Dragons for a few weeks in third grade, but I think the character alignment system is pretty easy to understand. Characters in D&D can be lawful, neutral, or chaotic, and they can also be good, neutral, or evil. This results in nine moral alignments: Chaotic Good, Pure Neutral (neutral-neutral), Lawful Evil, and so on, as shown below:

It’s not clear to me how much D&D has to do with it, but it seems to me that you can see the idea of this alignment system veined through the American social space. My Facebook feed, for instance, is regularly full of memes that celebrate Chaotic Good, the general pattern being: “I’ll blunder through a conversation, I don’t know where my kids are, and all my stuff spills out of my house the minute you open the door — but, heck, I’m tryin’!” There’s an accompanying understanding that Lawful Good people can kind of be pills, but they’re still good, so whatever.

Meanwhile, there can be Lawful Evil people and Chaotic Evil people, and there are true neutral people who, in this system, emerge as particularly morally interesting. If lawful people can be a bit of a stiff drink and chaotic people can be a bit of a handful, if it’s hard to be truly good, and if everyone wrestles with a bit of evil in them, what about person who is neutral along both axes?

Recently, though, it occurred to me that the moral alignment system for characters in the Dungeons & Dragons role-playing game might actually be an incomplete moral theory . . .

. . . And then, on the walk home the other day, it occurred to me that it becomes a much more interesting system if you rotate it forty-five degrees:

What if we suppose that Lawful Good is the absolute good, and Chaotic Evil is an absolute evil?

We’d definitely have to clarify what’s meant by Lawful Good and Chaotic Evil. Perhaps you could say that in the rotated system, absolute Lawful Good is a perfect balance of lawfulness and goodness.

But sometimes lawfulness is dogmatic and harmful, you might say. Yep. In that case is is not Lawful Good. The idea would be that the goodness in Lawful Good makes the lawfulness organic, true, and life-giving. Lawful Good represents conformity with a cosmic order, not a human one.

I notice that this principle underlies every major religious system, in fact. Certainly, the core of the Judeo-Christian tradition is that God’s peace is a lawful good. So, too, with Islam, along similar Abrahamic lines. I see it plainly in Hinduism and Buddhism, too. Cosmic harmony is a somewhat ordered phenomenon. That order defies human constructs, but it is ordered nonetheless.

But what about all those koans and absurdist statements in Buddhism? you might ask. Okay. But the purpose of absurdist koans is neither to induce nor to advocate for chaos, really. The purpose of absurdist koans is to shock the form-making part of the human brain into silence in order to allow a purer perception of reality — and one can readily suppose that that reality is expected to be somewhat ordered. Buddhism, like all major religious/philosophical systems, is a sprawlingly diverse entity, but there’s little doubt that, throughout, Buddhism is fond of order. In fact, as a systematic philosophy, it’s one of the most ordered systems there is — by a long shot.

Lawful harmony may not abide by laws that we find easy to model. But I think that there is actually a pretty reasonable article of faith: Cosmic. Harmony. Is. Somehow. Lawful.

Maybe another way to make the point would be to map the rotated alignment onto the American political system — which is what I did next on the walk home the other day. Clearly, this effort will be imperfect and it will reflect my biases. But I still think it’s helpful.

Barack Obama, I would say, would be the most outstanding modern example of Lawful Good. As a leader, he was positive, kind-hearted, compassionate, honest, self-reflective — all aspects of goodness. Also, he was organized, he followed the rules, and his administration was remarkably scandal-free — exhibiting, throughout, plenty of evidence of lawfulness. I’m reminded of when Sergeant James Crowley arrested Professor Henry Louis Gates in front of his home, and Barack Obama invited them to have a beer with him at the White House. To me, Obama honored the real dangers of racial profiling, while also honoring those we’ve charged with preserving law and order (attempting to clean up, in the process, an earlier remark that Crowley had acted “stupidly.”) To me this, like much of Obama’s presidency, was exemplary of Lawful Good — it honored both persons’ desire for ordered justice, but it did so in a way that emphasized connection, goodwill, and love.

I think you might also consider putting George Bush the First in this camp, too, and perhaps even Ronald Reagan — though I know people who would want to shout me down over that.

At the next tier, you have Lawful Neutral and Neutral Good. Lawful Neutral alignment involves an emphasis on the quality of lawfulness without the same attention to goodness, and Neutral Good involves an emphasis on the quality of goodness without the same attention to how orderly it is. And the big thing to notice, I’d say, is that it doesn’t seem to me that either of these are preferable to Lawful Good as described. And if they aren’t, then I think that that alone justifies the rotation.

To me exemplars in the direction of the Lawful Neutral archetype (i.e., people who are “lawful,” but perhaps not always superlatively good) might include Ilhan Omar — who I think is a competent legislator and constructive social thinker but who I also think is, notably, neither always totally socially circumspect, nor always kind. Also, perhaps Mitt Romney — who I would say is a lawful person, and who has taken some notable moral stances but who is also, I think, notably deficient in his understanding of the plight of the underserved. You might even consider putting Mike Pence here, I suppose — I’d say that Mike Pence is not entirely lawful, but I think in his own mind he intends to be, and perhaps he believes that he is succeeding as best as one could at it in the world today. Also, his lawfulness is definitely not entirely good, as he he has substantially enabled the person who is likely the most despotic and destructive political figure in American history. (That’s not good.)

Neutral Good people, people who are definitely “good” but who are not always so orderly about it, might include folks like Elizabeth Warren and AOC, perhaps. Both, I would say, are good-hearted, intelligent, competent fighters and both are, perhaps, not so morally disciplined as to be able to see some of their own partisan biases. It would definitely include our current president, Joe Biden — who is no slouch when it comes to the subtleties of systemic governance, but is also the person about whom President Obama said, “Never underestimate Joe’s capacity to f*ck things up,” and is the first public figure I have ever seen fall up a flight of stairs.

At the next tier, you have Lawful Evil, True Neutral, and Chaotic Good. Again, I think it’s worth noting that none of these alignments seem (to me anyhow) to be preferable to anything in the previous two tiers. Also, it seems to that the tension between Lawful Evil and Chaotic Good is one of the definitive tensions in American politics. One of the movements of contemporary conservatism, for instance, seems to be to attempt to preserve American social order by saying the unkind things that “everyone is thinking” (whether “everyone” is actually thinking those things or not). Meanwhile, it seems to me that American liberalism emphasizes unity without always taking a close look at the social rules that might underpin any such unity.

To me, the American exemplar of Chaotic Good is of course Bernie Sanders. I don’t know that there is a particularly visible example of Lawful Evil in the American political scene, but the authoritarian vein of the Republican Party definitely has this vibe to it. Internationally, you might consider Patriarch Kirill of Moscow, an orthodox Bishop who extols Vladimir Putin as an exemplar of Christian mission. (Thereby missing Jesus’ point, I feel.) And one can notice that there are several forms of uncanny association between certain forms of evangelized conservative American authoritarianism, and Kirill’s.

Even without exemplars, I think you can see the tension between Lawful Evil and Chaotic Good plays out frequently in American politics. For example, a few years back when the public started to pay more attention to the flagrantly disproportionate number of Black people who have died at the hands of police, many conservatives appeared to ignore the injustice altogether, and rallied around a “Blue Lives Matter” campaign, while many liberals demanded that we “Defund the Police.” At the extreme, the former stance exhibited an utter disregard for the plight of fellow human beings for the sake of a status-quo version of law and order, and so I think you might fairly put it in the “Lawful Evil” camp. Meanwhile, at its fringe, I think the latter stance could definitely be blithe about the complexity of the law and order issue (including the fact that, even in cities with the most vehement BLM protests, many people living in vulnerable neighborhoods both decried police violence and, also, still said they wanted a greater police presence on their streets). So I think you might put “Defund the Police” in the “Chaotic Good” camp (perhaps even verging on Chaotic Neutral). (Again, I’m probably revealing some biases here.)

At this point, I’m starting to get uncomfortable using concrete examples, because I feel like it might inflame more than illustrate. And, I dunno, maybe the most accurate diagram would be rotated only thirty degrees — so Chaotic Good ends up a little higher than Lawful Evil. And then maybe the center of American conservatism would need to be raised up above Lawful Evil. (It’s not hard to imagine that there are good-hearted conservatives who might feel alienated by the suggestion that conservatism at its core advocates for Lawful Evil. )

But I hope that a basic idea emerges. Currently, there is a strong vein of American social conservatism that is fronting lawfulness without great regard to whether it is good or not, and there is definitely a vein of American social liberalism that is fronting ideas about goodness without necessarily carefully considering whether or not they are lawful, in an archetypal sense. Each one of these then tends to demonize the other, with liberals saying that conservative visions of lawfulness are fundamentally evil, and conservatives saying that liberal visions of goodness are chaotic — and therefore evil. The underlying assumption of each camp is that the best thing to do is to refuse the other and choose themselves. And I think it’s worth noting how the rotated alignment figure reveals how obtuse that thinking actually is.

Of course, the rotated alignment also distinguishes a fourth compass point that I think is also in play in American politics — Chaotic Evil, which I would unapologetically associate with leaders of the MAGA movement like Lauren Boebert, Marjorie Taylor Greene, and, outstandingly, Donald Trump. This is a political movement without kindness or code. It is incredibly destructive. And, at present, I think it only really has visible exemplars on the political right. This greatly complicates the political map, because it means that in America, conservative stances are more often founded in ignorance and misinformation, and so the conservative opposition to liberalism is perhaps more substantially based in misinformation than the other way around.

Altogether, American politics becomes largely a dynamic involving the eastern, western, and southern points of the diamond. An over-arching narrative might go something like this: Conservatism drifts into a lawful movement somewhat unconcerned about its goodness, and then from within it erupts a vein of Chaotic Evil. Conservatism attempts to harness the Chaotic Evil for its political power and largely fails, because the Chaotic Evil overcomes it. Meanwhile, liberalism takes a stance against evil lawfulness and Chaotic Evil, without noting its own drift toward an increasingly chaotic system (and some Lawful Evil tendencies as well, in the more immature and severe courts of “cancel culture.”)

Above all this, though, I think one particularly fruitful concept in the rotated alignment diagram emerges: The top. The suggestion of convergence. In this model, what beckons above all is Lawful Good.

Neither goodness nor orderliness are morally neutral. Lawful Good calls Lawful Evil to goodness, and it calls Chaotic Good to lawfulness. So as each of these seeks its natural fulfillment, they tend to converge.

And I think that’s true. I think that Lawful Goodness is an important, and overlooked concept, a baby thrown out with the bathwater in the 20th century.

So instead of overlooking it, my suggestion would be to look at it.