Allowing America to break up a little might help keep it together.

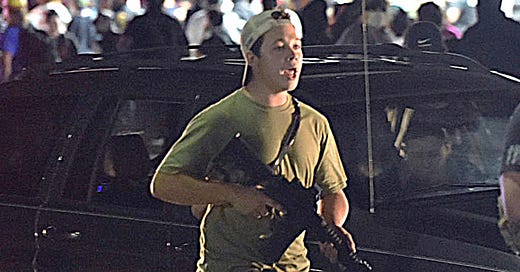

I’ll confess that I haven’t followed the Kyle Rittenhouse case as closely as it could be followed, and in the wake of his acquittal this week, I am just now beginning to sift through the nuances. As I look at the social media traffic one thing stands out me, though, which is that many people at large seem to me to be taking relatively definitive stances on the case, and that the more broadly definitive the stance, the more I feel that it lacks sufficient nuance to be taken to be the truth.

I’m not sure that rushing to conviction in a case like this is helpful. It seems to me that the most honest thing to say is that most of us are still digesting this case, and I wish that is what people said more often about more issues.

However, I do think that there are some more definite statements that can emerge from something like this, which are helpful. And if so here’s one I’d suggest:

Maybe it’s good to stop expecting America to be quite such a single, uniform, homogenous place.

My mother is from coal-mining country in western Pennsylvania, where my grandmother and grandfather lived their whole lives, and where aunts, uncles, and cousins have lived most or all of their lives, too. The afternoon before the start of hunting season, the administration at the local high school sometimes plays a collection of voicemail messages over the intercom of teachers calling in sick on the first day of hunting season. There are active, good-willing people who plan on deer meat helping them cut costs through the winter.

A few years ago, I went with my Uncle Ray to Christmas mass, and as I got into his large white pickup truck I noticed a box of rifle shells sitting on the bench seat between us. It startled me. He noted my reaction, and he teased me a little.

I said that where I was from if somebody had a gun, what they were going to shoot with it was a person.

That startled him. He said, “You know, I never thought about that before.”

I can certainly imagine how I would feel if what happened in Kenosha, Wisconsin had happened where I live. But do you know what day-to-day life is like in Kenosha, Wisconsin? Or what the prevailing cultural flavor is like, or the prevailing values are? I don’t. Kenosha, Wisconsin is a place far away from me. In some ways it’s an exotic, foreign place from my perspective. Sometimes I wonder if it isn’t fundamentally helpful, and fundamentally respectful, to allow it to be so.

Owning a gun in some parts of the country, for instance, can be quite a different thing from owning a gun in other parts. Carrying a gun in the open can be seen to be quite different, too.

Being seventeen in the affluent suburban periphery of a city (where upper middle class helicopter parents believe the streets to be more or less teeming with white vans waiting to scoop up any stray child immediately) can be quite different from being seventeen in other parts of the country (where, for instance, seventeen is genuinely seen as the threshold to adulthood, a time when one will increasingly shoulder genuine family responsibilities).

Zoning, permits, safety laws all have a different feel. And community, trust, peace, and violence, can all have substantially different connotations in different places. It seems to me that it’s worth trying to metabolize all of this.

Numerous recent events — particularly the past year — suggest that there are a startling number of people in America who are increasingly willing, out of their national political views, to imagine violence and to act violently. It seems likely that Kyle Rittenhouse’s acquittal will be amplified in mass media, fanning the flames, and more violence may result. So certainly local politics can have national consequences, and they can be taken to be genuine proxies for larger cultural tensions.

Also, nationally, it’s hard to imagine a black person receiving quite the same lenience as Kyle Rittenhouse did. It’s even hard to imagine the same percentage of black people as white people would feel free to show up at the Kenosha protests with a rifle in the first place. It seems clear to me that the Rittenhouse verdict salts these kinds of wounds across the country — particularly when the protests themselves were against the police killing of a black man — and I can understand why it would salt wounds, and I think there’s reason to engage this as a nation.

And to be clear, I think that Kyle Rittenhouse made a universally bad decision. I think that his motives were questionable. I think that he should be held accountable for the deaths that he caused, and I think that he was not sufficiently held accountable for his actions.

But also, it’s worth noting the extent to which the national culture war can be, fundamentally, largely an abstraction — a collision of things that are essentially mainly thought forms enclosed in a concept of nation that is itself mainly an idea, and which leads us away from more realistic and perhaps more imminent forms of national harmony.

Just as a thought experiment, if the inclination arises to look at something like the Rittenhouse verdict and say, in one way or another, “Look at what’s happening in America, where I live,” I think it’s interesting to instead say, first, “Look at what happened in Wisconsin, which is a different place from where I live.” And to really inhabit that and see how that feels before thinking about it in terms of larger circles of relationship.

As I inhabit the nuances with this framing, trying to consider a local perspective, my position changes. What at first glance looked like the classic teenaged product of the culture war tearing into a situation where he didn’t belong and getting away with murder — yet another unfortunate victory for the wrong side in a grueling culture ware — begins to become a more complicated dialectic about colliding values that has not yet been worked out.

I begin to wonder whether the thing that really needs to happen in Wisconsin is that people who more used to perceiving white boys with rifles as a threat need to talk to the people who are less used to perceiving white boys with rifles as a threat and try to understand each other, and to see if the laws couldn’t be reworked so that the next time a scenario like this occurs there are clearer, better rules that mind the interests of all but that definitely result in everyone walking away alive.

That becomes much more a story of a comparatively smaller place navigating contemporary concerns that it has not typically had to deal with, in a regrettably increasingly violent world — a situation that it seems to me can be more easily approached calmly, through reasonable dialogue, and one in which healthy discussion could easily be sabotaged by folk charging in and clubbing one another with partly-formed convictions that have been quickly tempered in the now long-burning fires of the larger culture war.

The red/blue divide in America is to no small extent also a city-mouse/country-mouse divide. And both city mice and country mice will continue to exist, to be quite different from one another sometimes, and to have, perhaps, a still great deal left to learn about one another. That’s worth minding, I have no doubt.

We’d do well to try to be a nation, for sure, and a nation needs commonality — especially commonality of values. And I am not suggesting that, in the name of diversity, anybody ought to condone activity which they viscerally feel to be wrong. But I also think that by cultivating a habit of seeing American events not as national events, but as local events, first, we might actually be more inclined to the kind of clarity that makes a live-able national unity more easy to achieve.