Better Human Relations Through Facebook Memes *

* Not really. But some (brief) thoughts following the SCOTUS ruling on affirmative action.

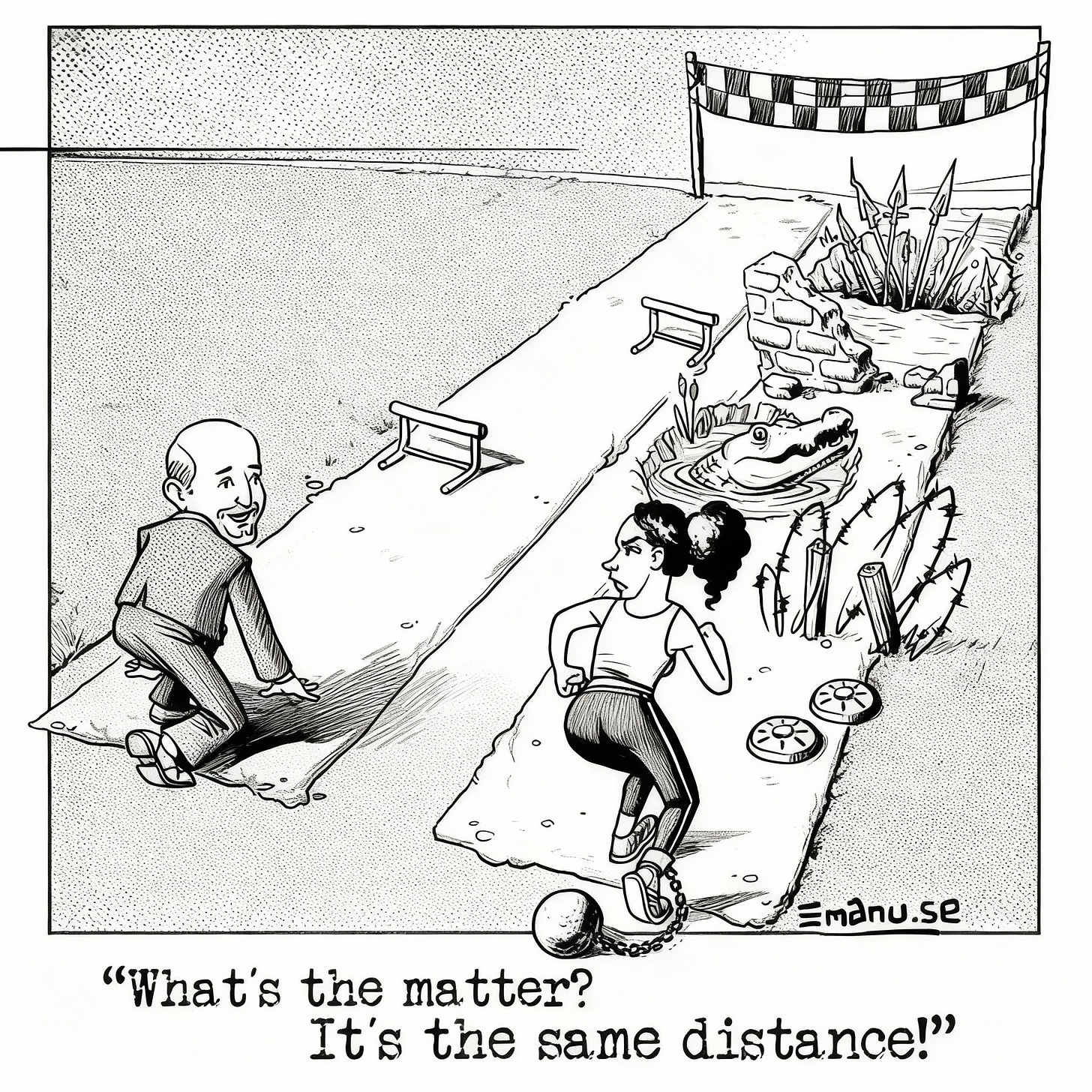

Today a Facebook friend posted the cartoon below, a fairly succinct commentary on the nature of privilege:

The message is clear and, it seems to me, valid: if you’re young, and/or a woman, and/or a person of color in the US, you face obstacles that you wouldn’t face if you’re old, white and male. And if you’re old, white and male, and you don’t acknowledge the differences, then you’re seriously ignorant about the realities of life. The message needn’t be quite so on-the-nose about the demographic categories involved — though I think that these particular demographic stereotypes aren’t totally false, either — but it’s definitely meant to be a comment on the nature of privilege.

America, it seems to me, and perhaps humanity at large, is in a very nascent stage of understanding the nature of privilege and what to do about it. It’s certainly good that the conversation has begun. And I feel aware, too, of the fact that there seems to be a good bit further to go.

Another friend on Facebook this week pointed out that on the of the challenges in the conversation about equity is that the benefits of privilege are often subtle or, as he put it, “intangible.” This seems to me to be an important thing to think about, because it seems to me that the cultural-war battles over the appropriate ways to get equity have a lot to do with whether or not we have a deep understanding of what privilege really is and how it affects both over-privileged and under-privileged people. It’s clear to me that affirmative action efforts are valuable, and it seems likely to me that the SCOTUS ruling constitutes a setback in the journey towards real equity. But also, I think it’s continually worth considering how often, in one way or another, we are considering what amounts to a change in policy as a way to address something that is actually much more nuanced.

Throughout the world, and perhaps particularly in in the US in some ways, one of the factors that particularly distinguishes between over-privilege and under-privilege is outright racism. Some people will dismiss other people outright on the basis of their skin color or other distinguishing characteristics — in ways enables them to become in both overt and subtle ways, the gatekeepers of other people’s well-being. This, alone, can take on very insidious forms, but on some level it might be addressed through affirmative-action-like policies. Do the demographics of an institution correspond to the demographics of the surrounding culture? If not, why not take some very general steps to increase the demographic diversity? Sounds like a good idea to me.

But obviously, the essential wounds that arise between over-privileged and under-privileged people can be much more subtle, and can persist even past the elimination of the more gross forms of discrimination.

I think of the most insidious of these, and one of the most broadly applicable, is this:

If I am in one way or another privileged, then you are accountable to me for your shortcomings in ways that I am not accountable to you for mine.

This seems to me to be one of the most destructive frictions that lingers even after ostensibly non-discriminatory policies, or hiring practices, or admissions practices might be in place, even after the diversity training and other steps to build awareness. If you and I meet across some gap of interpersonal difference, and your accountability for that difference is greater than mine, then a basic, fundamental injustice to you occurs. It’s a very simple friction. But even 101% and 99%, compounded again and again, produce very different outcomes. Even small frictions, over time, produce wounds.

What policy corrects for things like that? Ultimately, I don’t think any mere policy can. A general spirit of affirmative action, whereby sensitivity to racial issues is admitted as a salient factor in decision-making, seems to me to be an obvious step in the right direction. But it also seems to me that the most lasting remedy is a much more thoughtful process.

On one hand, if I and another are trying to connect across our difference, it’s important to establish the extent to which we have a general agreement about what constitutes the good. Are we both thinking carefully about what goodness is — especially apart from merely what it means to be personally gratified? If either one of us is not in the habit of rigorously seeking the good, then our ability to connect is definitely going to be impaired.

It’s especially worth establishing some kind of agreement about the pursuit of the good, perhaps, because for privileged people, dominance often looks and feels like righteousness — even when it isn’t.

And what if we disagree about what’s good, who’s to finally say what is good? You? Me? Some rough, thoughtless average of the two? Some mutual lapse into a forced moral agnosticism and lassitude? It’s a difficult issue to address. And it seems to me that it’s one that can’t be adequately addressed without some basic commitment to moral rigor on the part of all parties. Often enough, the idea of moral rigor falls off the table, it seems to me, and it shouldn’t.

But, also, it seems clear that a basic moral template is insufficient. We are all subjective judges, and we are all incomplete, and the models we create will be, too. And because whatever moral architecture we might articulate may be lacking, itself unjust, despite our best efforts, we need something else to keep us connected, related, zig-zagging toward the top of the mountain: a healthy practice of mutuality. Also this week, the following meme showed up in my feed. It’s a classic scene, with the dialogue reversed. (I’ve kind of awkwardly dropped into the post here — translated to line art by OpenArt.)

I think this silly meme is actually a surprisingly keen demonstration of the power of mutuality. Mutuality requires self-reduction and humility. It requires charity and an organic, generous acknowledgment of the other. It requires a deep sense of personal accountability. And it requires the ability to tell the story of the other accurately and well.

Folks seeking equitable relations should be rigorous about seeking the good, no doubt. But folks seeking equitable relations should be just as rigorous about the effort to charitably understand one another’s experiences — in order, from that understanding, to develop organic, mutually life-giving relationship.

There can be many good policies that constitute essential building blocks in the direction of a more beautiful world of mutual understanding. But it seems to me that it must not be overlooked that the real prize requires a more refined process of interior development. There are plenty of people who get all the bullet points right who also get the subtler stuff wrong — without noticing.

A truly better world is a more contemplative world. It’s a more intersubjective, more mutual world.