Christianity in Seven Propositions

Or, the Church that I would not attend conditionally, but really sit down in.

(In a way, this post is still about the Wesleyan quadrilateral, because in a way it’s talking about tradition.)

As I continue to study Christianity and work within a Christian framework, I am struck by the incredible value of finding community within some sort of explicit framework. Being in intentional groups is important. Being in intentional groups that are trying to grapple with the most basic existential questions is especially important. I think we tend to underestimate the extent to which this has been a normal part of human life throughout history, how it is less so now — and how unusual that is.

Nowadays, many people see intentional groups either as silly, stale, traditionalist religions, or as woo-woo cults. But that’s neither what they intend to be, nor what they have been, nor, entirely, what they are now. Intentional spiritual groups, including traditional religious groups, are supposed to be ways to get people organized, productively, around the most basic existential questions. It seems to me we often underestimate the extent that these structures do help us engage the most basic existential questions — even when the structures seem stale. I also think we’ve underestimated how poorly we engage the most basic existential questions without them — and, consequently, how much our lives have filled with junk.

At the same time, many critiques of these groups — especially the religious traditions — are valid. Many critiques of the Christian tradition are valid. I think the question is not about how far one can get within the Christian tradition, using it as a sort of primer, before you eventually graduate from it and have to seek transformation through another method; I think the question is whether a reasonably critically-thinking person can fully inhabit the tradition at all anymore.

I was writing about this in a grad class recently, and my professor suggested that it’s impractical to think of Christianity as a single thing, but rather to think primarily in terms of Christianities. This makes sense to me. Christianity is sprawling, and it is definitely not one practice. But I still feel — perhaps naively — like I want to try to identify essential mechanisms in Christianity — kind of the “synthetic division” version of Christianity (for the two percent of you who remember the math you took in grade school).

Here, I’m not going to pretend I’m discovering what essential Christianity is, I’m just going to talk about the Christian container that I would feel fully comfortable in. That container is oriented, essentially, around seven, maybe eight propositions. And I really think that a good approach to these seven (maybe eight) propositions is a great blueprint for any vibrant Christianity going forward.

God

I believe in a panentheist God. Theism is a belief in God. Pantheism is a belief in that God is in everything. Panentheism is the belief that God is in everything while also transcending it all, and remaining somehow ineffable beyond it. I’m convinced that this latter idea is the one that’s real.

When talking about the panentheist God, I would keep the idea from Paul Tillich that God is “the ground of all being.” And I would also keep the profound idea from the Judeo-Christian tradition that that “ground of all being” not only surpasses us in every way, but is also uncannily personal. The idea that relationship with God is deeply personal, and God can be characterized by perfect, but very personal goodness and love. I’d keep that. Not because I’m fond of it, but because I think that’s real.

Holy Spirit

To me, the idea of the holy spirit is essentially just a logical extension of the idea of a panentheist God. In his manifesto Unbelievable, Bishop John Shelby Spong argues that we should do away with the idea of (apparently) physics-defying miracles. I’m not sure we should. But I do feel that we should continue to explore this idea of a higher divine within us, and the idea that God interacts with our consciousness. This seems to me to be what the Holy Spirit is.

Adjacent to this is the idea of angels, spirit guides, and other discarnate beings. I think it’s reasonable to entertain these, too. But above all of that, it seems to me to be appropriate to entertain the idea of a Holy Spirit.

Jesus

I think there’s an inescapable need to work both with a “Jesus of history” and a “Christ of Faith.” This kind of distinction was long ago and repeatedly denounced by the Church as heresy. But I don’t know that it’s territory that can be avoided. At the very, very least, I think we should stop pretending that these can be easily treated as the same. As far as I can see, they can’t.

The Gospels are wonderful, fascinating literary works, worthy to be treated as sacred. But the arrangement of each Gospel is, in some ways, clearly a curation to make a point. And those points differ, somewhat. And even the basic events in each Gospel can’t always be jibed with the events in the others. And the census that sent Mary and Joseph to Bethlehem is hard to explain. And historical evidence suggests that prisoners crucified by the Romans mostly remained on the cross. There are dozens of questions about these pieces of writing and, to me, an unmistakable, and unbridgeable air gap between them and historical fact. We must be clear-eyed, open-hearted and savvy about this, I feel.

At the same time, I think the narrative at the heart of the Church, including the Christ story, is a profoundly effective way of salvation and transformation. I think the Christ archetype, the “cosmic Christ” as Richard Rohr puts it, seems to be some sort of real figure in the universe, with incredible saving power. Jesus was a singular mystic, and the idea that he was the Son of God, walking on Earth is itself profoundly transformative. Both Jesus’ life, and the nature of Christ can be explored. They can be held as overlapping. And I think Christianity for the future ought to allow each of them to move freely and frictionally relative to the other, and to find more and more effective ways to talk about that.

And, until the clearest language for distinguishing them emerges to fully embrace this process, perhaps as though waiting — as though in a new Advent.

Sin

Rolling around in the mud is not necessarily the best way to get clean, and history has many iterations of Christianity in which the emphasis on sin is excessive. But a savvy attitude about sin is important. It’s inevitable that we will miss the mark. Let’s be comfortable and real about this, and keep it squarely in view.

A savvy attitude about sin reveals that a certain amount of contrition and repentance are healthy and essential. Interpersonal contrition, systemic contrition, and contrition toward God. And capacity for repentance requires a habit of repentance. The essential Christian proposition, I think, is that we think about all of this, and talk about it, and let that make us wiser and wiser.

Sanctification

Julian of Norwich said that we are of the “nature” of God, but not of the “condition” of God. The idea of sanctification is the idea that, through a relationship God, we are become more surrendered to a higher will, and we are rendered more in the image of what God intends us to be. In other words, we’re made to be in more harmony with divine principles. It changes the way we feel inside, the way reality feels, and the way we actually are. I say keep all of this.

In the modernity, the idea of sanctification has generally been replaced by psychological models of wholeness, individuation, and mental health. I say keep these, too. I think Christianity needs a model of sanctification that is as robust as the psychological models of wholeness. I think we should seek one.

Church

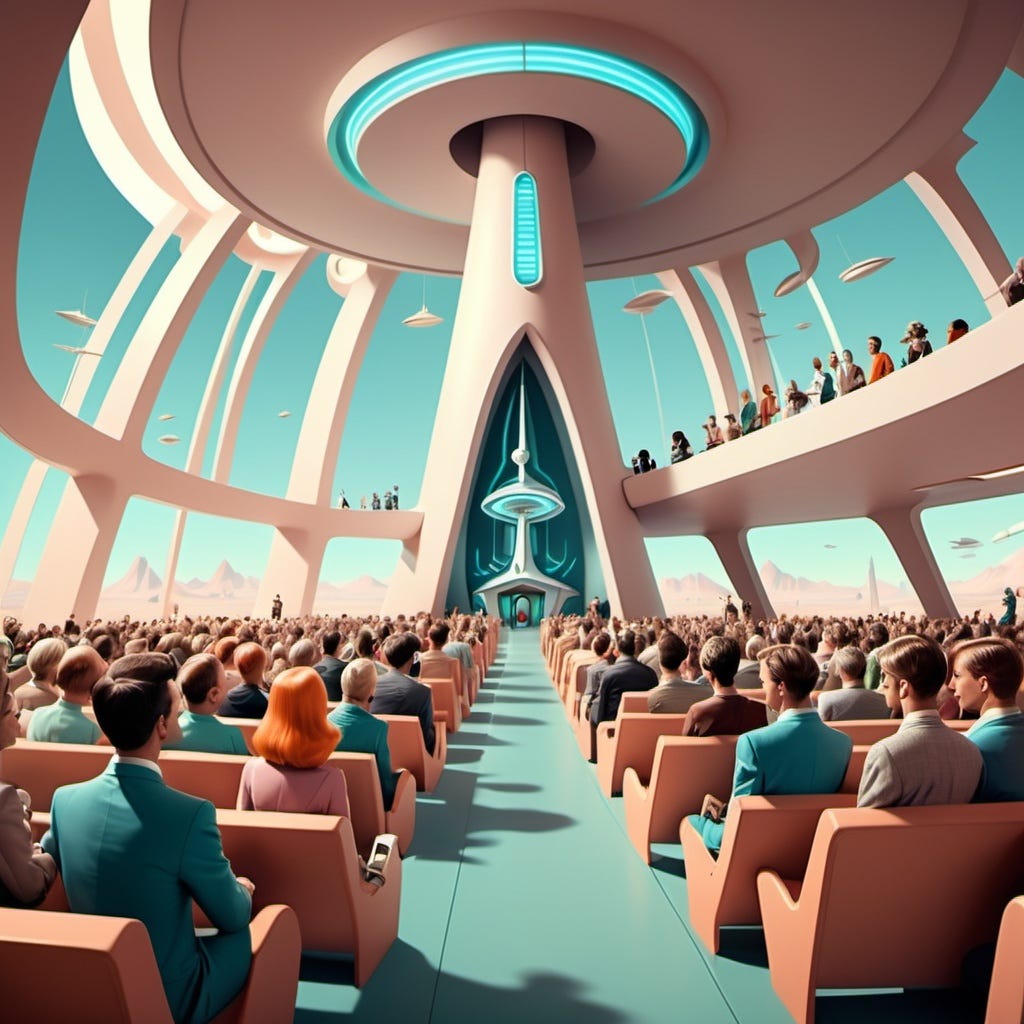

It’s been said that Christianity without group process isn’t Christianity. I think this is very, very true. Gathering in community with people who agree to the same set of propositions is essential. It doesn’t have to be a bad cult. It can be a good cult. Or something. But there should be groups, church.

Kingdom

This is a catch-all for a wide range of ideas. But basically, that we’re here not just to minister to each other in small ways, but to build mechanisms for a better world. The idea of kingdom comprises:

Committed personal practice that leads to:

Thoughtful, charitable interpersonal relations, and

Stewardship of larger-scale organizations and even societal systems

Right relations in our lives. Foot-washing, self-abdicating service. Care for the poor; the orphan, the widow, the foreigner. True, clear-eyed racial justice.

Kingdom forces us to think about the difference between “the life of the flesh” and “the life of the spirit.” The idea is that there are two ways to build on Earth. One way corrupts and the other way transforms. I think it’s important to know the difference.

To me, “Kingdom” also comprises ideas about the afterlife. The principles of Kingdom are operant not only here on Earth, but in an inconceivable expanse of realms beyond the physical world. I think the revelations of near-death experiences, visions of Swedenborg, and curious, fascinating writings like the Chico Xavier books are all worth considering as we develop the vision of a heavenly kingdom. A healthy Christianity would be able to incorporate the on-going revelations related to this.

As usual, I think there’s more to say. But this is probably a good place to stop. This is the more or less the Church that I am always looking for, I think. Much of what I write, and would write about Christianity, is basically developing these ideas.