Experience

Wherein sanctification and shadow work become friends . . .

Last week, I started talking about the Wesleyan “quadrilateral,” of spiritual discipline informed by scripture, tradition, reason, and experience. I was thinking that in a time of relative disorder, it’s important to think about rubrics, and how the Wesleyan quadrilateral is a useful one. It occurred to me that its four “corners” are particularly esteemed by four distinct, somewhat frictional cultural tribes, and that a more thorough integration of the four corners is important.

This week, I’m thinking about “experience.” When John Wesley talked about experience, he was talking about a certain kind of personal transformation. Wesley strongly believed that initiation into Christian practice was a progressive, but decisive new birth: “. . . [W]hen the love of the world is changed into the love of God; pride into humility; passion into meekness; hatred, envy, malice, into a sincere, tender, disinterested love for all mankind. In a word, it is that change whereby the earthly, sensual, devilish mind is turned into the ‘mind which was in Christ Jesus.’" The idea is that the Christian life should be a palpable, progressive process of sanctification, not simply an intellectual or faith-based concept of being “justified.”

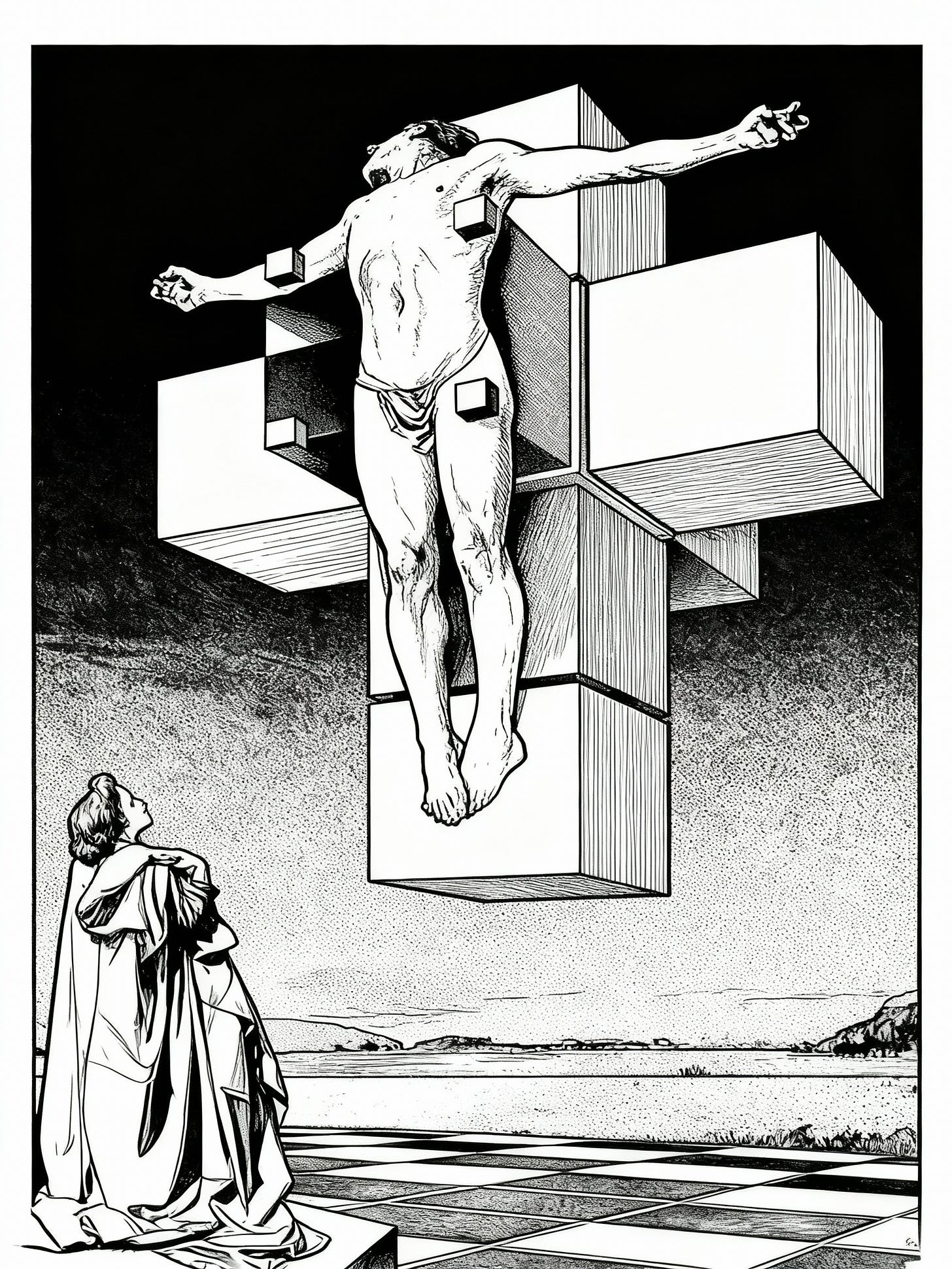

This notion of sanctification — particularly, in my experience, as it was developed in the 17th and 18th centuries by folks like John Wesley and Jonathan Edwards — is to me the core of Christianity — and, from a yogic perspective, perhaps one of its most distinct and interesting features. The idea is that personal growth necessarily involves a participatory act of divine mercy, initiated by the ground of reality itself, and evinced by the story of a perfectly-human, perfectly-divine being dying on a cross for the sake of uplifting the rest of us. (Worth noting that this proposition can be pursued while making a distinction between the “Jesus of history” and the “Christ of faith” — which I actually think is an essential distinction to make.)

A common tenet in the idea of sanctification is that, in our fallen state, we have lost the ability to properly sense value, because our perceptions have been contaminated by the original human “fall.” We need touchstones by which we can pull God’s “signal” from the “noise” of day to day life; to push back on the unregenerate parts of ourselves, and to provide a “rule” that helps us draw the straighter line of growth. Traditionally, the Bible is trusted to be the truest of these touchstones.

This also makes a certain amount of sense to me, actually — to an extent. When I think about holiness, I feel like I can sense into a world of being that is more elevated, more pure, more saturated, and so on. It feels to me that, somewhere, this world of being is real. Also, as I think about that holiness, it becomes increasingly plausible to me that there is indeed a kind of contamination of the perception of value, because I’m definitely not seeking that kind of holiness all the time. Also it’s clear to me that it’s possible to use the Bible, and other spiritual writing, as a way to connect with this higher world of being, and to find one’s way to better alignment with it. I think this a powerful idea that needs to be treated carefully, but I think there’s something to it.

Also, though, the idea that we can’t trust ourselves had led to really reductive ideas of spirituality. It’s clear is that a lot of damage can be done to people’s mental health and long-term development when religious authorities and/or communities have too stringent a definition of what is and isn’t pure, what is and isn’t righteous. The idea of holiness itself can create a profound state of alienation from oneself and from others — which is exactly opposite of the message of the Gospel. It’s easy to find versions of Christianity with this tendency — or, at very least, to imagine them, which alone makes them surprisingly real states that one’s consciousness can occupy.

Many people know this on some level, particularly folks who tend to give churches a wide berth. One of the prevailing social arguments of the past fifty years or so has been that organized religion is bad, because it’s repressive — and though I think there’s some tendency to straw-man churches, I think there’s a kernel of truth in this, too.

What if, instead of top-down religion, we act like the human psyche is itself divinely dynamic, and therefore sacred? There emerges an invitation to treat the “text” of ourselves as a sacred text, and to read this text carefully, i.e., to authentically inhabit our own experience for the sake of wholeness.

Traditionalists often see this line of thinking as a collapse into self-willed egotism. The notion of “living one’s own truth” is satirized as purely solipsistic. Those criticisms aren’t totally off-base, either, I feel. Generally, there seems to be a very poor integration of two “also goods.” On the one hand, traditions can trample a sacred inner dynamism, and on the other hand there’s a kind of self-justification that leads to a flaccid, self-serving, laissez-faire mindset that is increasingly characteristic of Western industrialized societies. Or, a saturated, kind of “thirsty” spiritualism that is ultimately conducive to commodification of self and other.

It seems to me that our accumulated folk wisdom falls short of our needs in both respects, and the prongs of the avant garde, such as they are today, are often going in opposite, and therefore inherently partisan, incomplete directions. On one side, there’s individualism that honors certain kinds of wholeness but tends toward hedonism and solipsism, and on the other, you have traditionalism that really taps into certain kinds of holiness, but which esteems doctrine in ways that tramples people, stunting them and the groups they belong to.

I think, at the very least, there’s an on-going need to integrate the most viable models of Christian sanctification with what’s called “shadow work,” i.e., the work of healthily embracing and integrating the parts of the self that don’t fit with the idealized self.

There’s a spiritual teacher named Saniel Bonder, who was a close student of Adi Da’s before he went his own way, who has developed a system of spiritual practice which he calls “Waking Down in Mutuality.” One of the core ideas of “Waking Down” is that enlightened consciousness doesn’t reject the lower parts of the human nature — it underlies, and comprises, them. Therefore, the path to awakening involves a deep, embodied inhabiting of one’s experience, not a rejection of select parts of it as “lower” or, in Christian terms, “of the flesh” — as though embodied life is merely some kind of inconvenient rind. The Waking Down movement has a variety of practices that are designed to help facilitate this process, including meditation, authentic sharing circles, and eye-gazing “transmission” sessions with more advanced practitioners — which all may seem a little woo-woo, but which, in my experience can all work to genuinely transformative effect.

It seems to me that shadow-work integration is really important. It would be great if Christianity began to incorporate it more: a vivid vision of the process of sanctification combined with a deep embodied inhabiting of all of human nature. I really think there’s something powerful there.

First, develop a healthy way to conceive of holiness. You can start with good, thoughtful reading — the Bible, the writings of the mystics, Emmanuel Swedenborg’s writings on heaven, Jeanne Guyon’s Experiencing the Depths of Jesus Christ, A. W. Tozer, near-death literature. Take your pick. You might also seek experiences in a church or a temple. If you belong to a place of worship, go there. If you don’t, you can shop for one — either in-person or online. If shopping, you can try some sources that you wouldn’t usually, including ones where you’re pretty sure you’ll have to chew the meat and spit out the bones.

Next, hold nothing back from that connection, by holding nothing about ourselves apart from our own awareness and by holding nothing about ourselves apart from that divine awareness, either. And this includes taking increasing calculated risks with how authentically we share our experience with other people.

This is the “Waking Down” idea: somehow all of our experience is part of a divine process. By opening to all parts of ourselves we can allow the fullest integration of ourselves, and also allow the process of sanctification to do its deepest, truest work.

Then, by opening these processes to one another, we can allow collective processes to work in our transformation. “Where two or more are gathered in my name . . . “ And so on.

I’ve been in very few spaces where it feels like people are practicing a full integration between this mindfulness of the holy and a full mindfulness of the integration of the shadow, but the glimpses I’ve had of this kind of dual practice suggest that it is incredibly powerful work with tremendous potential.

You might think. Whoa, that sounds like a lot. To dare to imagine and/or encounter something like a supreme cosmic holiness, and then to hold my messy, poorly integrated self in the presence of that? Doesn’t the bright light deepen the shadows? It feels like it’s too much to hold at once. Like I’d be stretched. Almost like I’d be laid out on a cross . . .

And perhaps there is some inevitability of a cross experience. Perhaps, also, the way can be easy and the burden can be light. At least some of the time.