The Hebrew Bible is full of stories. Let’s just let them be stories. I mean, it’s likely there’s some history in there. There’s a general acceptance that there may have been a flood at some point, for instance, and there’s stronger evidence for the Babylonian exile; the Torah had to come from somewhere, and the Israelites may well have come to Canaan from Egypt.

But also, there’s fairly robust scholarly consensus that stories about Jacob, Ruth, Daniel, and others are probably more like historical novellas. It’s hard to explain the census that would have had Mary and Joseph travel to Bethlehem. Etc. So, for the sake of the argument that follows, let’s just let them all be stories, without trying to litigate the historicity of the details.

Among these stories, there are many stories about disobedience and consequences. Adan and Eve in the garden. Cain killing Abel. God becomes unhappy with people and sends a flood. Later, the people of Sodom and Gomorrah mistreat angelic visitors, so God rains down fire and brimstone on Sodom and Gomorrah. Fleeing, Lot’s wife looks back. She’s turned into a pillar of salt.

In 2 Samuel, King Saul is deemed unworthy, and he is succeeded by David. David commits infidelity (the transgression is more the divine infidelity than the marital one), and he loses his mandate to be king. Throughout 1 and 2 Kings, Israel travels toward and away from God. In particular, there’s a lot of brouhaha about loyalty to the one true God, YHWH — and these transgressions have consequence. Solomon’s turning from YHWH causes Israel to fracture into two kingdoms. Ahab’s heresies bring drought. Manasseh’s heresies doom Judah to eventual conquest.

The prophets, many of them writing during the era covered in 1 and 2 Kings, continually associate misfortune with God’s judgment. Sliding in and out of God’s voice, Isaiah warns Israel:

Woe to the sinful nation,

a people whose guilt is great,

a brood of evildoers,

children given to corruption!

They have forsaken the Lord;

they have spurned the Holy One of Israel

and turned their backs on him.

Why should you be beaten anymore?

Why do you persist in rebellion?

Your whole head is injured,

your whole heart afflicted.

From the sole of your foot to the top of your head

there is no soundness—

only wounds and welts

and open sores,

not cleansed or bandaged

or soothed with olive oil.

It’s worth noting, too, that in many of these Biblical stories, when God metes consequence God also offers consolations of mercy at the same time. When Adam and Eve tell God they are naked, one of the first things God does is to make them clothes. When Cain’s sacrifice is unacceptable to God, God doesn’t really seem to think it’s a big deal. “Why are you downcast?” God says, “Don’t you know if you do well, you will be accepted?” After Cain kills Abel, when he tells God his exile will be too much to bear, God promises to protect him. When God sends the flood, God protects Noah and his family. After bargaining with God, Abraham hears that for the sake to ten righteous people in Sodom and Gomorrah, God will spare the cities.

God’s mercy is even more pronounced when transgressive people outright repent. Ahab eventually repents, wears sackcloth, and “goes about dejectedly.” He receives God’s mercy.

And in the same breath that Isaiah warns, he also pleads, in the voice of God:

“Come now, let us settle the matter,”

says the Lord.

“Though your sins are like scarlet,

they shall be as white as snow;

though they are red as crimson,

they shall be like wool.”

The New Testament speaks richly about repentance and redemption. In the Gospels, John cries out in the wilderness, “Repent! For the kingdom of heaven is at hand!”

Then Jesus shows up. He heals sin-induced illness, and he forgives people all over the place. He dines with tax collectors and sinners. He tells the story of the prodigal son, who squanders his treasures and returns to his father, ruined. His father welcomes him and throws a huge party. Jesus enthusiastically celebrates those who change their ways.

Again, let’s let the Gospels be stories, too. I think they correspond to some historical events to at least some degree, but still.

There are some good reasons to treat all these stories simply as cultural artifacts from another time. For one thing, some of the rebellious acts that bring God’s wrath wouldn’t seem that rebellious to us today. When the Israelites disobey God under Moses, it’s because they don’t ride into Canaan and kill everybody. When Saul falls out of favor with God, it’s because he didn’t completely wipe out the Amalekites. And in 1 and 2 Kings, when folks get into trouble because they turn to other gods, it’s not always entirely clear how much worse, or even how different, those gods were from Israel’s conception of YHWH at the time.

Generally, today’s societies are much gentler than Iron Age societies. Empire-level powers don’t crucify anyone anymore, like the Romans did. On a personal level, if you go against the will of another person, and that person gets angry and punishing and violent, we think of that as abusive, and we think that person has some personal work to do.

We listen to each other and talk things through. Many people no longer punish children the way people used to. We tend to celebrate our free will, and we celebrate tolerance.

We don’t think of God as a punisher, either. A God who extracts goodness by violence sounds like a bully. Bullies aren’t righteous; they’re broken, unhealthy, unhappy beings.

We don’t really like ideas of obedience and repentance at all. Obedient to whom? Repentant to whom? We associate these ideas with subjugation to one another — with a self-abdicating beholden-ness to the authority imperfect humans. Isn’t that a form of self-induced slavery?

I’d even venture that generally speaking Americans don’t apologize as a cultural rule these days. Or, at least, that we apologize less.

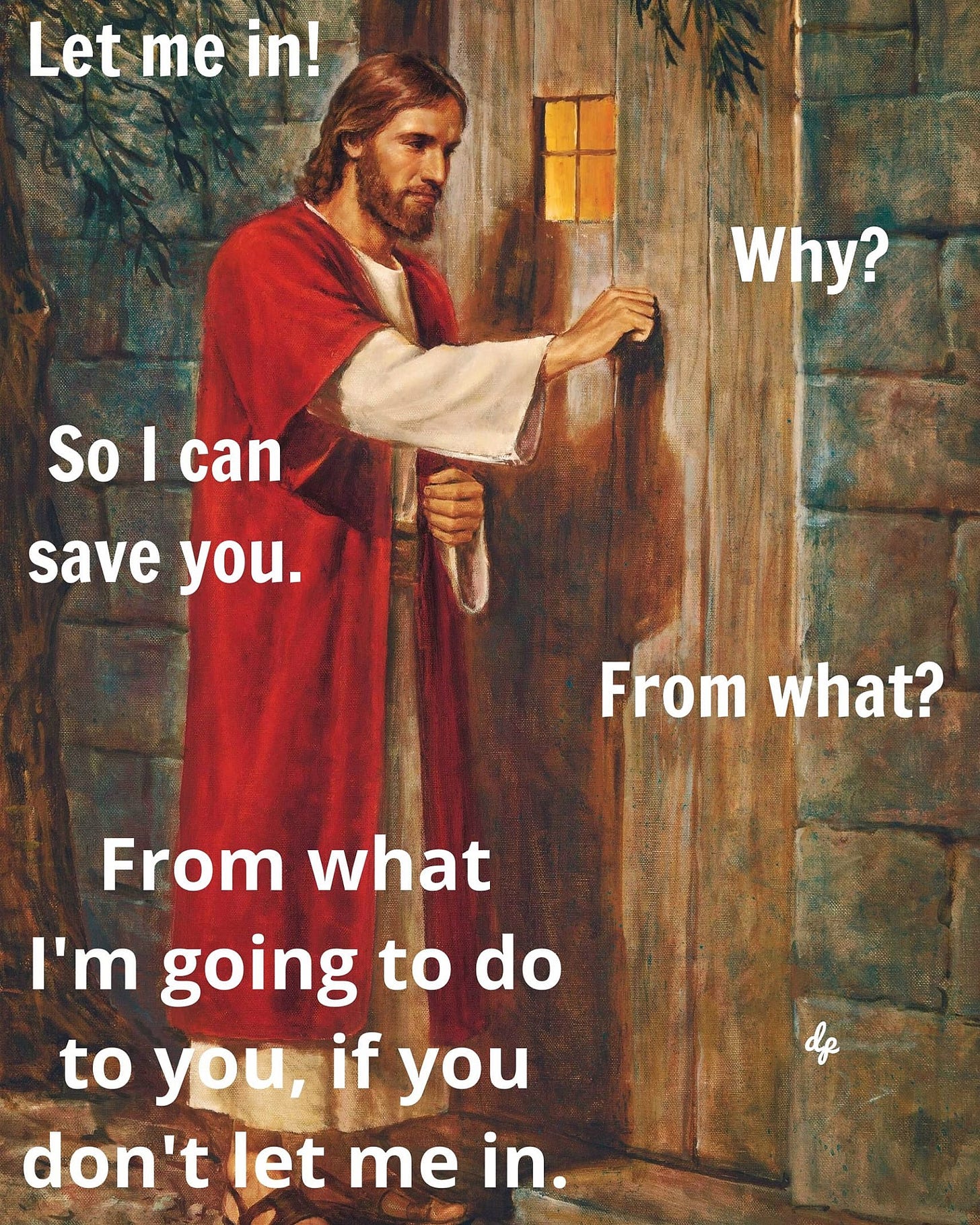

The whole Judeo-Christian arc starts to look a little ridiculous. It feels increasingly easy to poke holes in the theology. Facebook is full of (essentially straw-manning) memes like this one:

And not unfairly so. It makes sense to question the idea of a retributive deity, and the notion of retribution altogether. Our gentler relationship to transgression and consequence is genuinely more enlightened in many ways.

Also, though, when we think of repentance and obedience, we what we tend not to think to any great depth about what an actual God might actually be like. It’s easy to hear the confidence in the claims of the Hebrew Bible, and say, “I don’t think God wants me to kill all the Amalekites,” and to associate that kind of confidence with people who don’t know what they’re talking about.

Or, perhaps, we think we think about God. But if so, do we really think about God? Deeply? Many of authors of the biblical texts were proceeeding from the premise that God is the ultimate authority. What if we carry that idea forward, just by itself? What if we update that basic premise with our own understanding of reality?

Suppose that all consciousness arises from one consciousness, and that that consciousness is ultimate, and surpassing in every way? So much so, that every moment is actually perfect, and perfectly leveraged to evoke a transformation is us — and that that transformation can be done in continual consultation, in continual partnership, and in continual deference to that ultimate, surpassing consciousness?

And what if you carry forward the rest of basic premises outlined above? How ‘bout like this?

We are bounded beings. We cannot be and do everything. Something ultimate is aware of the bounds, and aware of optimal paths through those bounds to ever-greater consciousness. When we throw ourselves too hard against those bounds, we will contribute to adverse circumstances for others and for ourselves. When we return to that ultimate consciousness, it pours itself in, with grace, sweetness, intimate welcome, and wisdom, and mercy. All of this works for our good, always.

That’s the premise. And so what if we entertain this premise because it might, in fact, actually describe the nature of the reality in which we actually exist?

Let’s talk about verifiably real events that are occurring right now.

I’m writing the day after Hurricane Milton whipped from a Category 1 storm to one of the largest hurricanes ever recorded in the West, with staggering speed. Today it’s being called the storm of the century. It’s happening a little over a week after Hurricane Helene devastated Western North Carolina, washing out staggering swaths of mountain towns.

Some of the places that were hit with hurricane-force winds from Helene will also be hit by hurricane-force winds from Milton. In many of these places, the debris from Helene has not yet been cleared away. So Helene and Milton will not just be a one-two punch; Helene will have essentially armed Milton with extremely high-caliber ballistics of concrete, stone, wood, and steel.

We’ve known about climate change since the 1970s. We are a quarter of the way through the twenty-first century. For the entirety of that quarter-century, we have expected what is shocking us right now. We have talked, with surprising specificity, about exactly what is shocking us right now.

And we know why these shocking things are happening. We know very clearly why:

We have transgressed natural laws, through environmental degradation and emissions of heat-trapping gases.

We know our sin, too. We all know it perfectly well.

Our sin is greed.

And here come the storms. And here they will come. And come. We have said this to ourselves for many years now: The storms can be expected to get worse for hundreds of years.

Until . . . what?

Here’s something else that we know: Where humans practice greater environmental stewardship, ecosystems can rebound — sometimes surprisingly quickly. Where humans have practiced greater environmental stewardship, species long thought to be extinct have re-appeared.

“Though your sins are like scarlet,

they shall be as white as snow;

though they are red as crimson,

they shall be like wool.”

Sometimes, the crimson of extinction itself turns out to be the wool of life returning.

To be clear: I’m not suggesting we should all march ourselves to the nearest church, without any discernment, and subjugate ourselves to the first person in a robe we see there. Far from it.

I am suggesting, though, that maybe it’s time to bow down to something. To surrender to something. To turn away from something, and to turn to something. To put on some form of sackcloth. To make some form of sacrifice. To offer up some kind of new action.

Here’s what I’m saying: I’m saying that maybe some of that archetypal, wrath of God of Abraham thinking is actually a little apt here.

What if people with no sense of obedience at all, with no sense of repentance at all, are actually categorically unable to respond sufficiently to the climate crisis?

Maybe repentance and obedience are actually necessary capacities of healthy souls. And maybe they do invite mercy, purification, and grace. Maybe repentance and obedience are actually the tiny foyer to a much larger mansion of possibilities.

As long as we don’t try to completely wipe out the Amalekites, that is.

But repent to what, or whom? Obey what, or whom?

I think that, ultimately, it’s a matter of individual discernment. I would suppose we all live in the same reality. But I think we’re sovereign over our sense of what that reality is — and we should be. Through individual discernment, we can begin to articulate broader consensuses, which can help define larger community and cultural belief systems.

At the very least, we are obeying the dictates of nature. The dictates of hydrodynamics.

At the very least, we are repenting, essentially, to water.

Is there anything greater than water at work? That’s up to you to determine. Feel free to determine whatever you believe about cosmic law, cosmic heart, cosmic mind. Or a web of life that comprises all terrestrial beings. Let YHWH be merely a proxy for your own ontological primary, or let it be exactly what you think undergirds the universe. It’s the habit of bowing, with humility to that cosmic order — whatever it is — that I think is exemplary.

Perhaps the overwhelming suggestion is actually that, after the difficult surrender, we can actually pass through a surprisingly well-lit door into a surprisingly bright place.

In other words, perhaps grace is real.

If we repent, that is.

If we repent.

And if not, then what do we think is going to happen? From any frame at all, what do you expect is going to happen?

Because — let’s be clear — the storms are coming.

And coming.

And coming . . .