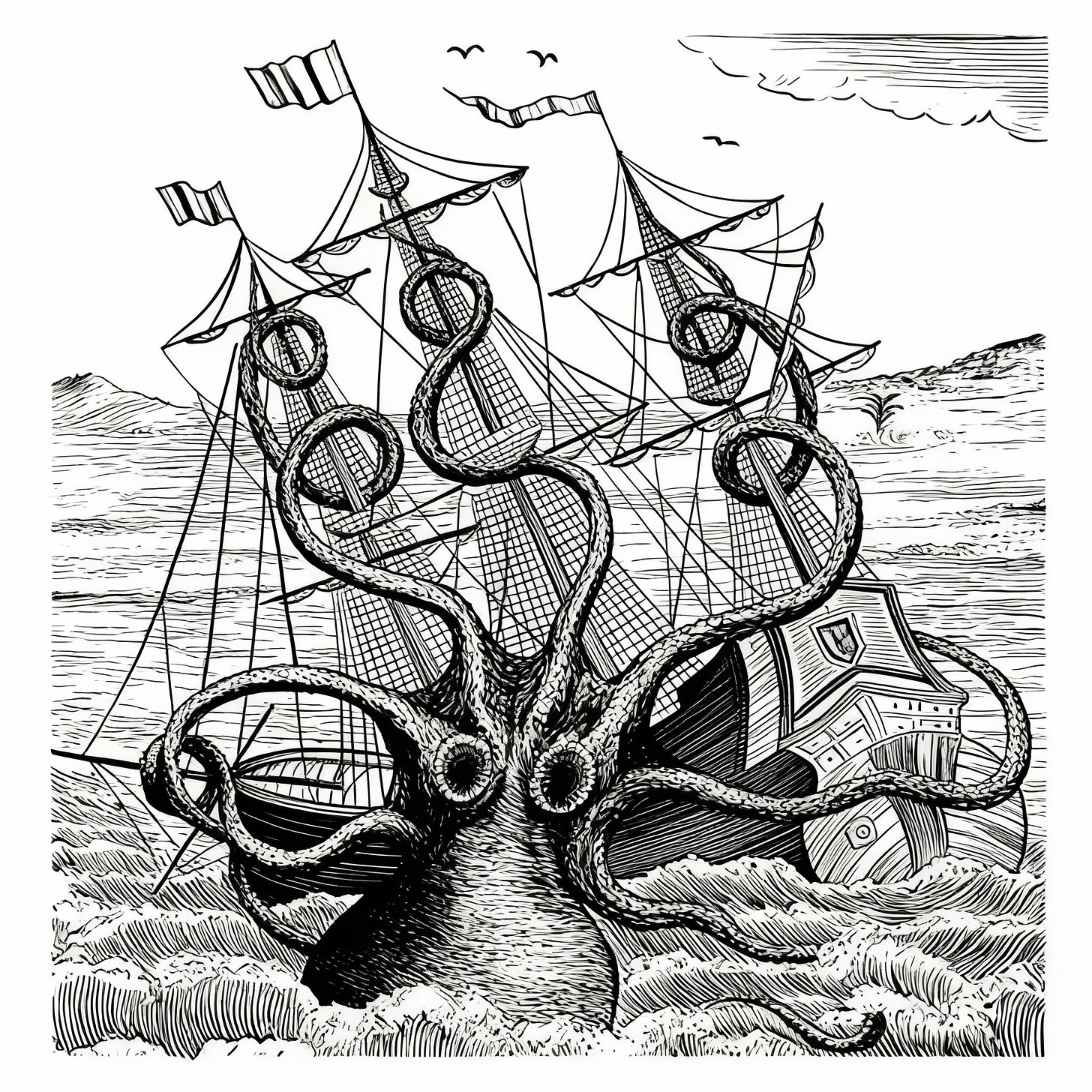

The Kraken and the Squid

What is real? Really. What is real?

The Kraken is a sea monster that drags ships under with its tentacle-like arms. It can swim rapidly in circles, slurping ships down in fierce whirlpools. The earliest account of the Kraken we have comes from King Sverre of Norway in 1180, and tales accumulated over centuries. It could get as large as an island. The sea monster itself could swallow ships and whales whole.

The giant squid is a cephalopod, described as early the first century CE by Pliny the Elder, who said it could grow about 9 meters long. Today, the male giant squid is believed to get as long at 10 meters, and the female as long as 13 meters. The giant squid is believed, of course, to account for at least some part of Kraken myth. In 2006, Japanese researchers first recorded one, nearly one thousand years after King Sverre, and two thousand years after Pliny. It’s still not clear whether giant squid is one species or as many as twenty. It’s still not clear how big they have ever gotten — reports range up to 18 meters. A great deal of mystery remains.

Which is more marvelous, the Kraken or the giant squid? In the most astonishing accounts, the Kraken could be as marvelously large as a land mass. But the giant squid is marvelously real.

For a century or more, the most widely respected way to define reality in the industrialized world has been a reductive materialism, which got called science. Eventually, there comes the belief that any idea that has any particularly mysterious life to it, is a Kraken, and you have to abolish it because it’s not the real thing, which is the squid. Anyone of a more romantic or mystical bent argues that too reductive a materialism kills something in the world — and the materialist replies that whatever is being killed is not real, so if you want to live in reality, then you have to let it die.

Undoubtedly, there’s some truth there. When we turn mythical Krakens into real giant squid, we are making more solid contact with reality. No doubt. But also, it turns out that industrialized consumption — the most definitive fruit of reductive materialism — is in fact literally killing the world, just as the romantics feared it could. In many ways, the environmental crisis is a direct rebuke of reductive materialism itself.

Surely, something more than a culture that kills the world must be possible. The Kraken may actually be a giant squid. But the giant squid is not a dead machine. It, too, like the Kraken, is alive, marvelous, still mysterious.

So what, then, are the true boundaries of the real?

We languish in our definitions of the real, whether we know it or not. Our day-to-day lives can be thoroughly cluttered with the mundane, and at the same time unmistakably haunted with fantasy. At my work, a learning institution, there is an inordinate amount of conversation about files — digital records of the learning process. Are your files properly formatted? Who’s checking the files? No one’s directly to blame; it’s a byproduct of the system that nobody likes and nobody’s been able to fix. But it does cause human attention to orbit around silly human artifacts. Actually, if you look at it, you might notice that the entire world of American education orbits silly human artifacts more than it should.

At the same time, the world of education is also haunted by lavish fantasies about human potential, and about teachers’ ability to generate it in the people who come through their doors. The distinctly American notion of a teacher is mythologized enough that in 2020, an entire nation fairly casually just expected teachers to invent an utterly historic new form of education. Didn’t ask, simply expected. And teachers did it. And people went on about their lives without particularly noticing what had happened. The Kraken-myth of the magical civilization-saving teacher appeared to persist. Perhaps one day, that myth will be revised to include the roil of burnout and resignations that resulted from real people pushed to supernatural limits.

Someone once told me that in America today, the average married couple with children speak to one another for fifteen minutes a day, and that that fifteen minutes is usually about logistics. Meanwhile, we can watch people love each other on TV — and then we can expect real people to love the way written people, played by actors, do. Again, we live between the too-mundane and the too-fantastic.

Both are Krakens. One is a mythology of romance, and the other is a mythology of dullness. In a world of the excessively mundane, one of the marvels people find most attractive is power. Perhaps this is a contrast effect. But people really like to rise above one another, don’t they? In a mundane world of isolation, we start to mythologize ourselves.

The Bhagavad Gita tells us, unequivocally, that we are luminous, extraordinary beings temporarily ensnared by a sensory experience — like sailors in the tentacles of the Kraken. Can we wake up? Absolutely, the Gita says. And people all over the world have fashioned Kraken-like fantasies about what it means to wake up. In the United States, enlightenment often entails a surprising amount of accessories, costumes, and retreats. Alternately, you can reject the notion of liberation entirely, and live in the material, seeking things and worldly power.

But does the high-blown, romanticized understanding of enlightenment have some generating seed, perhaps? What is real?

Jeshua, a rabbi in first-century Palestine, taught a radical doctrine and was executed by the Romans. People called him the Messiah. Very early, his followers articulated that his death achieved a novel and universally available restoration of humans’ relationship with their parental God. Anyone could access this salvation through faith in Jeshua, the Anointed, who through Greek translation became known as Jesus Christ. Some people take these messages of vicarious atonement very literally, while others, baffled, drop the idea altogether, leave that rabbi behind in those quaint tales set in ancient Palestine, and go back to the files, the logistics, the tangible things, the worldly power.

Still others contemplate more mysterious notions of a transforming spirit, of a salvation-like relationship “in Christ.”

What is real?

Fires in Canada fill the East Coast of the US with smoke. Last week, in DC, it was recommended one wear a mask outside for four out of seven days. Something vaguely apocalyptic is happening: slowly, perhaps, for now — but faster and faster. And how do we understand it?

Many of the images are mythical and Kraken-like: The Earth turned to Venus. Civilizational collapse.

Alternately, we ignore the problem altogether. We imagine nothing more sensational than files, errands, logistics. Perhaps we dream not of even of mythical creatures, but of our own power over others in a reductive, materialist world.

Both, Krakens.

What is real, what is real?

Do you see?

The question of Kraken and the squid is not an idle academic exercise. It’s one of the most important things we can do in our day-to-day lives.