Understanding the Hate, Part 3: An Integral approach

How Integral Theory can help parse the American culture war.

This is third piece considering the saturated hatred of the political left that haunts a great deal of conservative discourse in America — thinking particularly about the intersection of MAGA and Christian nationalism. Parts one and two can be found here and here.

Recently, after having spent about ten years generally pooh-pooh-ing Ken Wilber’s Integral Theory whenever it came up, I’ve gotten really into Ken Wilber’s Integral Theory. I first read Wilber in the early 2000s, and though I appreciated him then, I found him pretty dry, and I found his fondness for stage theories a little troublesome. Actually, more to the point, when I met his disciples I often found the way they embraced the stage theories to be troublesome. But I really like and recommend his most recent book Finding Radical Wholeness. Now I find his models to be grounding and reassuring, to be coming from a good place, essentially genius in their scope, and, most importantly, essentially valid.

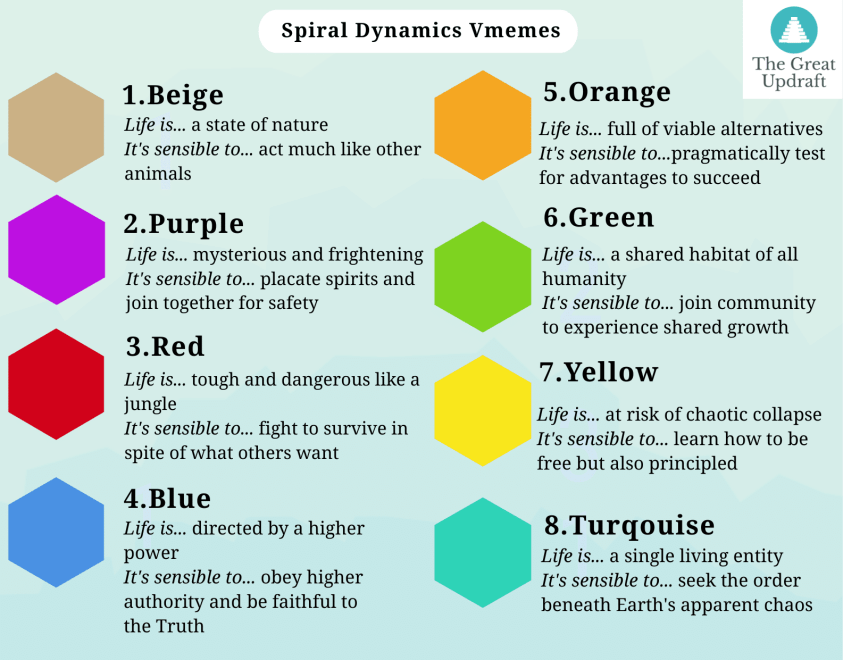

Of the stage theories upon which Integral is based, one standout theory is Clare Graves’ “Spiral Dynamics.” Below is a very — perhaps dangerously — quick summary of Spiral Dynamics, in graphic form. The basic idea is that human consciousness — both individual consciousness and collective consciousness proceeds through a series of stages, or “memes.”

There’s more nuance to each of the memes, and I’d encourage you to read about them. But if you’re not familiar, the graphic above might be enough of an orientation. A key component of the Spiral Dynamics model that each meme “transcends and includes” the one below it. There’s also the idea that, early in the process of evolution from one meme to the meme right above it, there might be friction with that lower meme, while a healthy, mature psychological progression beyond a particular meme is evinced by a tolerant attitude toward it.

Worth noticing that four memes in particular are easily visible in America today. Red, which emphasizes security created by the strongest in the group; Blue, which emphasizes a cosmic order established and overseen by a divine authority; Orange, which fronts empiricism and pragmatism; and Green, which emphasizes moral relativism and inclusion.

Astute readers might already begin to see how the meme structure can be mapped onto the American culture war. I think its uses are many. Wilber devotes a sizable section of Finding Radical Wholeness to discussion of partisanship in America, and I think his insights are some of the cleanest that anyone has articulated.

Among his observations, Wilber notes that there’s a strong vein of the American left that has embraced “Green” values of community and inclusion, in principle, without actually having fully transitioned into a tolerant, interdependent Green consciousness. So that ideological camp is attempting to establish Green values through a “Blue” mindset, through legalism and orthodoxy, treating inclusive, interdependent dynamics as rigid, easily-understood rules in a cosmic order, and resorting to “Red” tactics when necessary — seeing the fight for equality as essentially a struggle where only the strongest will prevail, and using whatever means to become the strongest themselves.

Meanwhile, Wilber says, there are veins of conservatism that are generally centered in a Red (power/struggle) consciousness or a Blue (authority God/lawful order) consciousness too, who feel forced into new levels of development by a culture that values inclusion, but has not fully matured into an inclusive mindset, either — but which has substantial clout because it, very demonstrably, enjoys relative hegemony in the culture at large.

I think stage theories need to be treated cautiously, as they can lead to reductive views of people, which I consider to be one of the worst things to do. Also, one of my main criticisms of Integral has been that it’s conducive to spiritual bypassing — i.e., that its fans sometimes round themselves up when they locate themselves in the hierarchy and sidestep the messiness and murk of their own spiritual work.

But also, I think it’s important to look at what gets teased out here. As you get further into the theory of Spiral Dynamics, you can start to see core faults in the way the entire sociopolitical discussion is being framed. Note, for instance, that Spiral Dynamics suggests a meme has to be fulfilled, in a way, before the progression to the next meme can occur. And while this development can be promoted and, perhaps, accelerated, it also has an organic quality to it. And, obviously, evolution of one person is somewhat beyond the will of another. So evolution can be promoted, in some ways. But in some ways, it takes as long as it takes.

Somewhat complicating the picture, Spiral Dynamics model suggests that first four, perhaps five, memes tend to be somewhat inherently self-centered or ethnocentric. “Ethnocentric” is being defined broadly here, not just in terms of race, but referring to a general preference for those that are like oneself. Wilber estimates that something like sixty or seventy percent of the global population is operating at a self-centered or ethnocentric level of consciousness. Like it or not, Spiral Dynamics argues, this is a long stage of development that people must move through — and if you want widespread social change, it suggests that this process ought to be shepherded thoughtfully.

As it is, I think it becomes easy to see why some people with more traditional attitudes, perhaps living in more out-of-they-way parts of the country, would embrace such “win at all costs” tactics in national politics: They act like they’re in an existential struggle, because they genuinely feel like they’re in an existential struggle — because they not only feel that they are being forced to accommodate value systems that are different from their own, but they genuinely feel that permission to be at their level of development is being taken away. To me, this is one keenest articulations about the American culture war I’ve heard. I think it is one of the most important insights about the whole situation.

It creates a difficult tension, obviously. Because though painful struggle America has argued itself to the bedrock understanding that racism is wrong, and is well on the way to arguing that other forms of discrimination — against gender identity, sexual orientation, limited physical or cognitive ability, neurodivergence, etc. — is wrong, too. How can you say that these forms of discrimination are wrong and, at the same time, say that some people are in developmental stages that are inherently ethnocentric? Isn’t that tantamount to saying that discrimination is wrong, but sometimes we have to allow it?

Or worse, is it tantamount to saying that discrimination is wrong, except when it isn’t?

To be clear, I do not mean to sidle up to the idea that any form of discrimination is okay. It’s not “okay.” But I would argue that a healthy approach to the American culture war is to not assume that the solutions are easy.

I’d note this affecting TED Talk by Sally Kohn. Kohn understands hatred from the inside, and she takes us, movingly, through her own childhood when she bullied another girl her age, talking broadly about hatred of the other as she goes. From the get-go, she confesses and repents. It’s an incredibly touching, humanizing thing to watch. And in the end, her solution is strikingly simple: We just need to create more opportunities for people to have genuine encounters across lines of difference, she says. It certainly sounds like a productive idea. And, she concludes, “That’s it.”

This seems to me to be a characteristic assumption of popular inclusion ideology. Just admit that resistance to difference is wrong, and include everybody. But is really that simple? Clearly, open-minded encounter with the other is a useful, even necessary thing, and I think probably some forms of xenophobia can be categorically rejected. But what about folks who, after having the encounter with the other, still prefer their own ways of doing things? And aren’t a lot of people that way?

In the activist left, I’ve noticed there are quarters where the prevailing assumption is that everyone being included is loyal to “Team Inclusion.” And certainly in parts of Western Europe and the United States, there are prevailing movements of plurality and colonial reconciliation, even a deep, wrenching wrestling with these issues. But it’s also worth seeing that, throughout the world there are many groups, including the prevailing cultures of whole nations, that continue to be homophobic, misogynistic, anti-Semitic, etc. Team Inclusion is a great idea, but it’s worth considering that there’s no inherent guarantee that even the newly-included beneficiaries will be inclusive themselves. Plurality is complicated.

It’s worth noting, too, that Spiral Dynamics not only helps us understand the mindsets that are contributing to the culture war, it also helps us envision what inclusion looks like. When we include, do we include everything and mush it all together, or do we include toward a structure which, itself, is better at handling complexity? As I’ve said before, the conversation about inclusion cannot be separated from a deep, careful conversation about values.

Past this, there are even deeper issues of culture and identity that can be treated increasingly sensitively. One might take a second look at the legal cases involving the business owner who refused to make a pink and blue cake for a transgender person, and the business owner who resisted designing websites for same-sex couples. Some basic precepts easily emerge. Let’s say, without hesitation, that it’s good if same-sex couples and transgender people enjoy full inclusion in society, including basic access to businesses services available to anyone, and it’s not good if they don’t have basic entitlements such as these.

But we might also consider what it means if people can be forced, by the state, to express or endorse views that run counter to their most-deeply held cosmological convictions. Whether they’re right or wrong, and whether we agree with them or not, is it really that hard to understand why someone in such a position might feel under siege, particularly if they can remember a time when their views were not so widely challenged? And that such a person might begin to feel a little desperate?

There’s an invitation to move beyond either/or thinking. Rather than thinking of this simply as a situation where an LGBTQ+ person gets their rights as a customer, OR a religious traditionalist gets to isolate in their traditional views about gender and/or sexual orientation, we can see that there is a friction with sharp edges on both sides of it. What if it’s reasonable to suppose that some substantial amount of people are naturally located at an “ethnocentric” level of perceptual development?

What if we don’t begin by trying to force it out of existence, but we begin by expecting it?

Again. This is not meant to be an argument against pluralistic, inclusive culture. But it is an argument that there’s value in openly allowing pluralistic culture to be as complex as it is — including finding a way to embrace people who are not great at opening to difference.

Ken Wilber has helpful, hopeful suggestions. Evidence indicates folks who are aware of developmental stage theories tend to progress more quickly through them, he says. Notably, when Ken Wilber says “evidence indicates,” it’s sometimes worth kicking the tires of that a little bit. But this idea bears out in my own experience, and I think it makes sense. He suggests that a good focus would be on creating developing more and more “conveyor belts,” i.e., institutional mechanisms that explore the idea of development and compassionately foster folks’ growth.

David Storey, professor at Boston College has observed that a healthy democracy (in Spiral Dynamics terms, an “Orange” actually entire relies on a robust foundation of “Blue” meme institutions, like traditional religion. Institutions like these, Storey argues, have multiple functions. They provide a solid moral primer for participants, and they also create assurances that there is broad social agreement on that moral primer. They reinforce the idea that order can exist apart from “might makes right,” and they can defuse some of the win-at-all costs approach to social phenomena. In other words, they serve as “conveyor belts’ from one meme to the next, of the kind that Wilber was advocating, and they set the foundation for transition to even more circumspect modes of thinking.

One might return again, from the first of these posts about MAGA, the Oklahoma law permitting religious instruction in public schools, and the Louisiana law requiring that the Ten Commandments be posted in every state educational institution. On the one hand, this is clearly regressive Christian nationalism. But what if in significant ways things like religious traditionalism is indeed part of the foundational anatomy of a healthy society? It’s still not great policy by the standards of modern liberal democracies. But it’s possible to inhabit the thinking of it a little further, I believe. And to understand how the partisan divide makes it harder for conservative ideas about social fabric and liberal ideas of social fabric “yes and” each other.

Ultimately, I think one of the deepest invitation that emerges is to view a nation as an organism. If a third of the nation roils with a “virus,” it’s perhaps worth not thinking purely in terms of how “they” are afflicted, but how “we” are afflicted. And I think it becomes easier to understand how conservatives, a substantial swath of the population, but definitely a social minority, might start to feel that their share in the collective conversation is being abridged — why they might start to rally around increasingly radical, fascist, totalitarian ideologies to try to be seen and heard. And why they might get angrier and angrier as they have to do it.

Recall that in 2016 about a third of the electorate was reduced, by the Democratic nominee, to a “basket of deplorables.” Without condoning the MAGA movement, I think there was always more there to see.

It’s important to keep a person who has casually threatened the end of democracy from holding office. But also, it seems to me that the amelioration of the American culture war fundamentally relies on not trying to vote the MAGA movement off the island, which is impossible, but through holding it somehow — toward healing of the whole, toward the evolution of the whole, not toward the victory of one side of the organism over the other.

And to do hold, I feel, we must labor to understand.